Washington Would Cross This River

In the dead of winter on the western banks of the Delaware River, a regiment of soldiers shivered and huddled in the dark. This ramshackle army of farmers and blacksmiths had just retreated from a string of humiliating defeats where they were outnumbered, outgunned, and out-led. The camp numbered in the thousands but it was quiet as a grave. Only the howl of a chill wind and quiet grumbles of exhausted men kept the night company. The revolutionaries were at the edge of mutiny; desertions were soaring; frostbite and disease were rampant. The weeks before, civilians would jeer at them in the streets, so indignant they were at the new army’s poor performance on the field. Each man clung to a dimming hope that seemed to fade a bit more with every passing hour, every lost friend, each toe amputated and left in the snow.

Across the river, the victorious British army and its sellswords were celebrating a grand victory. The American rebels were defeated and no longer able to muster effective resistance to Imperial British might. With the onset of a particularly harsh winter, the campaign for the year was over. They garrisoned the city and set up a string of outposts, distributing their troops with intent to hold the territory. It was Christmas Eve and the messy business of war was behind them.

But among the citizens of occupied New Jersey there was much sympathy for the revolutionaries. Reports of lax security started to make their way to Washington, scattered rumors of vulnerabilities in British fortifications, places where men and material could be potentially moved in secret with sufficient haste. An idea for a bold winter offensive began to form in Washington’s mind.

Washington’s Army was in a dire state, and he was not certain that it was up to the task. Washington was a stern and even-tempered man, not prone to poor moods, but he was wracked with doubt at his capability, and he feared for the nation that he swore to defend. “I think the game is up,” he confessed to John Caldwell, one of his most trusted lieutenants.

Embedded in that same army was a well-known writer. “These are the times that try men’s souls ... ” he scrawled into parchment in the field, trying to capture the emotion of the moment. He was serving in a capacity that we would recognize today as a War Correspondent, or if you are less kind, a revolutionary propagandist. He marched with the army, enduring the same hardships and struggles, and would then write about conditions on the front, reporting to both Congress and the general public about the War. His name was Thomas Paine.

Paine was an avid supporter of the revolutionary cause and wrote about it extensively. He wrote the pamphlet Common Sense earlier that year. It sold over 100,000 copies in the first few months, with estimates of over 500,000 sold in the first year if you consider British and French audiences. During the retreat that led to the continental army’s near and seemingly imminent defeat, he penned a short essay named “The American Crisis” on his thoughts about the revolutionary cause. It was published a week earlier on December 19th.

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”

The American Crisis he spoke of was the potential for failure of the revolutionary army and a rallying cry to push hard once more, despite the pain, the terror, and the fear of loss. It was about desperation and conviction in a time of existential conflict, and the delta between those who have strength to pursue unlikely ends and those who wilt in face of something that feels bigger than they are.

Washington was a longtime fan of Paine’s work, and he realized this essay was the final piece he needed for his plan. He was a prudent commander and some would argue too prudent. He did not have a particularly distinguished record in battle, but the task before him was enormous and he knew the fate of the nation hung on the choices he made. He also understood that morale is a strategic asset. He ordered the essay read aloud to all his soldiers on December 23rd, 1776. A war council of his top commanders met a few hours later and a decision was made to launch not a further retreat and likely dissolution of the army, but a dangerous and brazen attack. Preparations began immediately. An eclectic mixture of pleasure craft, ferries, and civilian fishing boats from local residents was haphazardly mustered on the banks of the river.

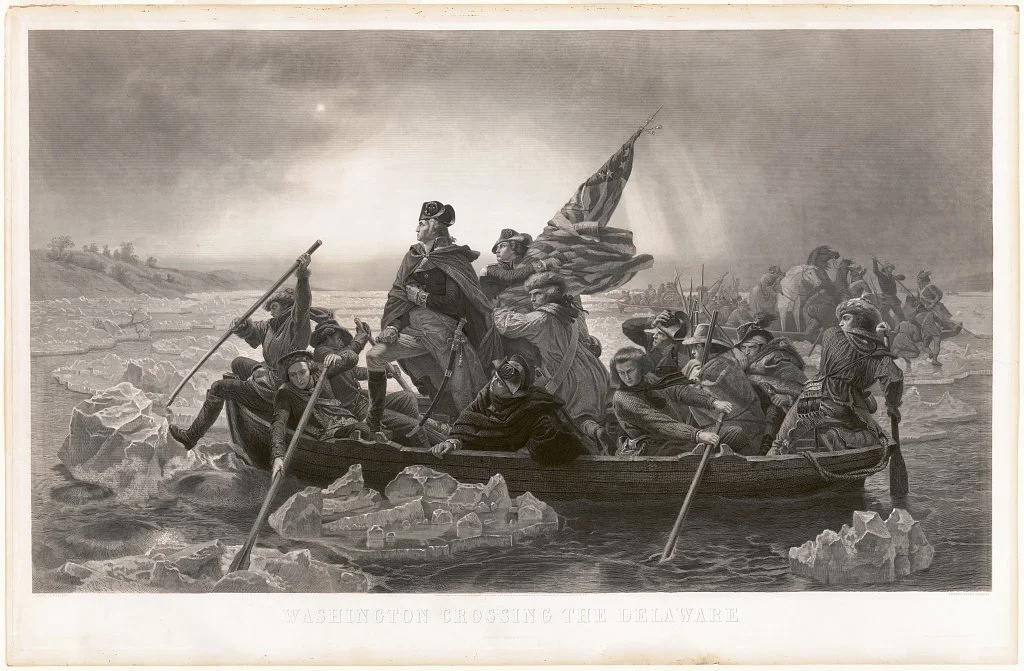

Two days later in the evening of December 25th—the impromptu river fleet sailed uncertain across stormy waters as a nor’easter passed overhead. Baleful winds rocked the fleet as the boats groaned under the load of horse, wagon, cannon, and warriors. Men fell overboard into icy water while dozens wounded by frostbite and suffering from starvation broke ranks on the other side, and could not march any further—though by providence and miracle not a man lost his life fording that treacherous river on that treacherous night. The crossing took hours and delayed the attack ‘til the morning of the 26th. The storm proved a boon however, because it compressed the intelligence available to the British and allowed for the stealthy movement and placement of artillery, scouts, and companies of men.

Washington and 2,400 men stormed an enemy outpost staffed by Hessian Mercenaries at the edge of Trenton. Using pre-positioned artillery, they bombarded the enemy garrison, cannonades firing fusillades from the cover of winter into the heart of the enemy's resting strength. The snow and the cold made it impossible for the mercenaries to muster an effective defense. Muskets got wet and failed to fire correctly because they had not weatherized their equipment. The desperate operation turned into a rout, though only about 20 Hessians were killed, 100 wounded, and about 1,000 more taken prisoner.

Victory assured, the revolutionaries took account of their victory. The first thing they looted were the boots, to replace the rags on their feet that bedeviled the ill-equipped army for over a year. Food and wine were taken, to fill bellies and warm souls. Bandages and medicine were found to help their wounded, and shelter from the storm secured so that at last they could get at least one good night's sleep in a warm bed. Stories of the victory spread like wildfire, and quickly turned into tall tales. Recruitment soared. The newspapers of the new nation boasted of the army’s triumph. A laughing stock of a military became heroes overnight. Congress was able to get the votes required to increase funding and secure more equipment and support. Washington achieved legendary status as a war leader of brilliance and boldness.

The French became very interested in using the rebelling colonies to annoy their longtime adversary, and in time, money, material, and expertise flowed into the fledgling American Nation from Europe. The admittedly small victory created the conditions for further success. They later went on to win two more battles and drove the British out of New Jersey. A few long years and many battles later—the British were caught between the Americans on land and the French at sea. The Battle of Trenton—over a small outpost with a few thousand men on each side—changed the course of the war, and of history.

I tend to think in military analogies; I find there is great wisdom about tactics, strategies, and human psychology in the stories of history and war, and they are applicable to all domains where there is contest or struggle. The lesson here is that even when you are tired, the path to victory for any challenge in war, business, or politics is through the use of overwhelming force at the weakest point you can find. An army at the edge of dissolution demonstrated courage and resolve at the right time, against a soft target and reversed the fortunes of a war whose consequence was the birth of a great nation.

Had Washington not crossed that river, I cannot say with confidence we would have won our independence. He found and successfully navigated the difference between courage and prudence, and was able to execute on both. Strike, and strike hard when the moment is nigh—but always with an honest accounting of strengths, weaknesses, and the balance of forces available to both sides of the conflict.

We now stand at the banks of an icy river. The agents of the government are beginning to suppress, slowly but surely, all forms of organized resistance. Corporations are paying bribes directly to the administration through blatantly corrupt crypto schemes or tariff exemptions. Media institutions are buckling under the weight of lawsuits and threats while agents of the new crown harass citizens in slowly increasing numbers. The economy teeters on the edge of collapse as capital and labor start to flee the country for safety. It does not look good for the resistance, you might argue.

Though it is ascendent in the government and continues to consolidate illegitimate power, politically the MAGA movement is fracturing and falling apart. The MAGA agenda is wildly unpopular. Trump's poll numbers are sliding by about a point a month, and every point drop represents a million and a half people moving from supporter to ambivalent or from ambivalent to active opponent.

The government is in disarray and that dysfunction is causing harm all across the country. Basic functions like disaster aid or national security systems are starting to fail. Dozens of Republicans are planning early retirements. Mike Johnson is out of tricks and couldn’t keep the Epstein files from being released. They have of course cheated using redactions, but a major leak is likely and what we are already seeing in them doesn’t look good for the President. The America First Movement is riven by weaknesses and infighting, and more than a few MAGA die-hards have already begun the process of trying to scrub their reputation so they can say they were one of the good ones when the tides finally turn.

But remember for every bit of exhaustion we feel our opposition feels it ten-fold. We are tired through exertion. They are tired because whatever good part of their soul is left rebels and revolts against what they have become in service to mere power without principle. They believe they are victorious and yet they panic constantly. MAGA is fundamentally a reactionary force—it spins like a broken compass—pointing with confidence but never towards a real destination. Locked into the internal now and without vision or leadership, they are distracted, they are unaware, and their defenses are down.

Thomas Paine said it best:

“Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as Freedom should not be highly rated.”

As we enter this new year of trial and sacrifice—remember that our history is full of such stories, of ordinary people who have achieved incredible things in the most dire of circumstances. We do this work because it is the province of the courageous, and it is a strategic necessity that we do so. Washington would cross this river.

Bryan Winter can be reached via Bluesky (@savingtherepublic.bsky.social) and Facebook.

Enjoyed this article? Get updates on the movement, volunteer opportunities, and more by clicking below.